Revue de presse de l'Histoire - La Seconde guerre mondiale le cinéma les acteurs et les actrices de l'époque - les périodes de conflits mondiales viètnamm corée indochine algérie, journalistes, et acteurs des médias

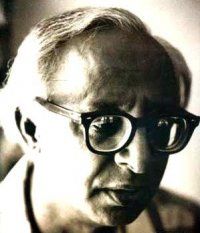

Srinivas (1916–1999) was an Indian sociologist. He is mostly known for his work on caste and caste systems, social

stratification, Sanskritisation and Westernisation in southern India and the concept of 'Dominant Caste'. Srinivas earned his doctorate in sociology from the University of Bombay and went on to

the University of Oxford for further studies. Although he had already written a book on family and marriage in Mysore and completed his Ph.D. at University of Bombay before he went to the

University of Oxford in the late forties for further studies, his training there was to play a significant role in the development of his ideas. Srinivas served in various institutions of repute

like University of Delhi, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Institute for Social and Economic Change Bangalore and National Institute of Advanced Studies Bangalore. Srinivas died in 1999

at the age of 83.

Srinivas (1916–1999) was an Indian sociologist. He is mostly known for his work on caste and caste systems, social

stratification, Sanskritisation and Westernisation in southern India and the concept of 'Dominant Caste'. Srinivas earned his doctorate in sociology from the University of Bombay and went on to

the University of Oxford for further studies. Although he had already written a book on family and marriage in Mysore and completed his Ph.D. at University of Bombay before he went to the

University of Oxford in the late forties for further studies, his training there was to play a significant role in the development of his ideas. Srinivas served in various institutions of repute

like University of Delhi, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Institute for Social and Economic Change Bangalore and National Institute of Advanced Studies Bangalore. Srinivas died in 1999

at the age of 83.

In his Frontline obituary he has been described as India's most distinguished sociologist and social anthropologist. His contribution to the disciplines of sociology and social anthropology and

to public life in India was unique. It was his capacity to break out of the strong mould in which (the mostly North American university oriented) area studies had been shaped after the end of the

Second World War on the one hand, and to experiment with the disciplinary grounding of social anthropology and sociology on the other, which marked his originality as a social scientist.

It was the conjuncture between Sanskritic scholarship and the strategic concerns of the Western Bloc in the aftermath of the Second World War which largely shaped South Asian area studies in the

United States. During the colonial era, the Brahmins or Pandits were acknowledged as important interlocutors of Hindu laws and customs to the British colonial administration. The colonial

assumptions about an unchanging Indian society led to the curious assemblage of Sanskrit studies with contemporary issues in most South Asian departments in the U.S. and elsewhere. It was

strongly believed that an Indian sociology must lie at the conjunction of Indology and sociology.

Srinivas' scholarship was to challenge that dominant paradigm for understanding Indian society and would in the process, usher newer intellectual frameworks for understanding Hindu society. His

views on the importance of caste in the electoral processes in India are well known. While some have interpreted this to attest to the enduring structural principles of social stratification of

Indian society, for Srinivas these symbolized the dynamic changes that were taking place as democracy spread and electoral politics became a resource in the local world of village society.

By inclination, he was not given to utopian constructions: his ideas about justice, equality and eradication of poverty were rooted in his experiences on the ground. His integrity in the face of

demands that his sociology should take into account the new and radical aspirations was one of the most moving aspects of his writing. By the use of terms such as Sanskritisation, "dominant

caste", "vertical (inter-caste) and horizontal (intra-caste) solidarities", Srinivas sought to capture the fluid and dynamic essence of caste as a social institution.

As part of his methodological practice, Srinivas strongly advocated ethnographic research based on fieldwork, but his concept of fieldwork was tied to the notion of locally bounded sites. Thus

some of his best papers, such as the paper on dominant caste and one on a joint family dispute, were largely inspired from his direct participation (and as a participant observer) in rural life

in south India. He wrote several papers on the themes of national integration, issues of gender, new technologies, etc. It is really surprising as to why he did not theorize on the methodological

implications of writing on these issues which go beyond the village and its institutions. His methodology and findings have been used and emulated by successive researchers who have studied caste

in India.

He received many honours from the University of Bombay, the Royal Anthropological Institute, and the Government of France; he has received the Padma Bhushan from the President of India; and he

was the honorary foreign member of two prestigious academies: the British Academy and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.