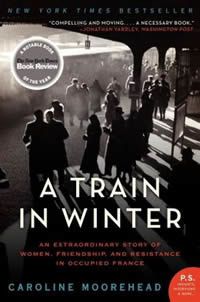

A Train in Winter

They were teachers, students, chemists, writers, and housewives; a singer at the Paris Opera; a midwife; a dental surgeon. They distributed anti-Nazi leaflets, printed subversive newspapers, hid resisters, secreted Jews to safety, transported weapons, and conveyed clandestine messages. The youngest was a schoolgirl of sixteen, who scrawled "V" (for victory) on the walls of her lycée; the eldest, a farmer's wife in her sixties who harbored escaped Allied airmen.

They were teachers, students, chemists, writers, and housewives; a singer at the Paris Opera; a midwife; a dental surgeon. They distributed anti-Nazi leaflets, printed subversive newspapers, hid resisters, secreted Jews to safety, transported weapons, and conveyed clandestine messages. The youngest was a schoolgirl of sixteen, who scrawled "V" (for victory) on the walls of her lycée; the eldest, a farmer's wife in her sixties who harbored escaped Allied airmen.

Strangers to one another, hailing from villages and cities across France—230 brave women united in defiance of their Nazi occupiers—they were eventually hunted down by the Gestapo. Separated from home and loved ones, imprisoned in a fort outside Paris, they found solace and strength in their deep affection and camaraderie.

In January 1943, they were sent to their final destination: Auschwitz. Only forty-nine would return to France. Drawing on interviews with these women and their families, and on documents in German, French, and Polish archives, A Train in Winter is a remarkable account of the extraordinary courage of ordinary people—a story of bravery, survival, and the enduring power of female friendship.

Fiche Technique

Fiche Technique

- ISBN-13 : 9780061650710

- Publisher : HarperCollins Publishers

- Publication date : 23/10/2012

- Author : Caroline Moorehead

Editorial Reviews

Editorial Reviews

From Barnes & Noble

Caroline Moorehead's moving narrative about the French Resistance has not one heroine, but 230. These brave women were Christians, Jews, and agnostics; teenage schoolgirls, professional women, a midwife, a singer, a dental surgeon, housewives, and communists. Most of them died at Auschwitz. A Train in Winter brings the stories of these courageous anti-Nazis vividly to life with manuscripts, primary, and secondary sources. Hailed as "compelling and moving....a necessary book" in hardcover; now in trade paperback and NOOK Book.

Booklist (starred review)

“Heightened by electrifying, and staggering, detail, Moorehead’s riveting history stands as a luminous testament to the indomitable will to survive and the unbreakable bonds of friendship.”

Caroline Weber

…by turns heartbreaking and inspiring… —The New York Times Book Review

Jonathan Yardley

…compelling and moving…Moorehead obviously likes and admires these women…but she does not romanticize them; they are real people, with shortcomings as well as strengths…The literature of wartime France and the Holocaust is by now so vast as to confound the imagination, but when a book as good as this comes along, we are reminded that there is always room for something new…reading A Train in Winter can be hard indeed, but it is a necessary book. —The Washington Post

Publishers Weekly

In an unfocused account, Moorehead relates the story of 230 women accused of being members of the French Resistance who were sent on one train to Auschwitz in January 1943; fewer than 50 survived the war. In fact, only some of the 230 were involved in actual Resistance activities. The youngest prisoner, 16-year-old Rosa Floch, caught writing "Vive les Anglais!" on her school's walls, died of typhus in Birkenau. Alsatian psychiatrist Adelaide Hautval was arrested after exhorting German soldiers to stop mistreating a Jewish family; she survived the war, but committed suicide after recording the horrors she saw when forced to participate in Josef Mengele's medical experiments at Auschwitz. Moorehead (Human Cargo) wants to recount how these women supported one another and to honor women of the Resistance, but she tries to tell too many stories about a highly diverse group of women, many of them not Resistance members. Though moving, the lack of focus may leave readers confused. Photos. (Nov.)

More magazine

“As chronicled by Moorehead with unblinking accuracy, their agonies are appalling to contemplate, their stories of survival and friendship under duress enthralling to hear.”

The Jewish Journal

"A miraculous story about friendship and the will to overcome extraordinary cruelty, heartache and loss."

Booklist

"Heightened by electrifying, and staggering, detail, Moorehead’s riveting history stands as a luminous testament to the indomitable will to survive and the unbreakable bonds of friendship."

Marie Claire

"Haunting account of bravery, friendship, and endurance."

Caroline Weber

"By turns heartbreaking and inspiring."

Meredith Maran

"[A] moving novelistic portrait. . . . An inspiring and fascinating read."

Natasha Lehrer

"An extremely moving and intensely personal history of the Auschwitz universe as experienced by these women. . . . A powerful and moving book."

Elysa Gardner

"[Moorehead] traces the lives and deaths of all her subjects with unswerving candor and compassion. . . . In Moorehead’s telling, neither evil nor good is banal; and if the latter doesn’t always triumph, it certainly inspires."

MoreMagazine

"As chronicled by Moorehead with unblinking accuracy, their agonies are appalling to contemplate, their stories of survival and friendship under duress enthralling to hear."

Judith Chettle

"Even history’s darkest moments can be illuminated by spectacular courage, such as courage that Caroline Moorehead movingly celebrates in A Train in Winter. . . . Moorehead has created a somber account, sensitively rendered, of yet another grim legacy of war."

Buzzy Jackson

"The first complete account of these extraordinary women and, incredibly, over 60 years later we are still learning new and terrible truths about the Holocaust. . . . An important new perspective. . . . Careful research and sensitive retelling."

Jonathan Yardley

"A necessary book. . . . Compelling and moving. . . . The literature of wartime France and the Holocaust is by now so vast as to confound the imagination, but when a book as good as this comes along, we are reminded that there is always room for something new."

Meganne Fabrega

"As Moorehead delves deeply into the women’s fight for survival, her narrative seamlessly comes together in order to share a significant part of history whose time has come to be heard."

Library Journal

The winter of 1942–43 encompassed some of the darkest days of World War II, not least for the French Resistance. Moorehead (Gellhorn) uses as her lens the lesser-known January 1943 transport of 230 women of the Resistance to the Auschwitz death camp. She conducted interviews with several of the 49 surviving women or their families and incorporates information from their published and unpublished works about the experiences they endured during their incarceration. Taking us from the early days of the Resistance and these women's roles to the postwar period of disillusionment and unhappiness, Moorehead finds inspiration in the way they assisted and protected one another, sometimes ensuring another's survival to the detriment of themselves. VERDICT Readers will get a good overview of the historical context and the sacrifices made by women whose motivation was to provide a better world for their country. Although at times difficult to read (the descriptions of Auschwitz offer nothing new but reiterate the horror endured), this book rightfully gives these women—survivors and nonsurvivors alike—their place in our historical memory. For a memoir by a woman in the Resistance not transported with this group, see Agnes Humbert's Résistance. [See Prepub Alert, 5/16/11.]—Maria C. Bagshaw, West Dundee, IL

Kirkus Reviews

Compelling stories of a group of brave French women in Nazi-occupied France. Of the so-called Convoi des 31,000, including 230 women political prisoners sent to Auschwitz in January 1943, only a handful survived to tell the horrendous tale of their plight. Biographer Moorehead (Dancing to the Precipice: The Life of Lucie de la Tour du Pin, Eyewitness to an Era, 2009, etc.) interviewed survivors of the convoy and tracked down family and stories of numerous others to reconstruct a fraught period in French history when collaboration was assumed the norm, while underneath seethed a current of active subversion. After the shock of the arrival of the Nazis in Paris in June 1940, the Vichy government advised the French citizens to cooperate with the Germans. While most French didn't protest the treatment of exiles and Jews, some did, especially idealistic youth who had been radicalized in the '30s by the Spanish Civil War.

One of the women, a dentist named Danielle Casanova, was the leader of a youth wing of the French Communist Party who recruited other young women secretaries and office workers as couriers of underground literature. With the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, resistance against the Nazis was ratcheted up and acts of sabotage were endorsed by the various factions of the Resistance. Unfortunately, the German spy network, aided by French police, grew more alert, and after attacks at the metro and in Rouen, Nantes and Bordeaux, traps were set and a sweep of "terrorists" netted by March 1942. The prisoners, both women and men, were first sent to La Santé, in Paris, where they were interrogated and tortured, then to the military fort of Romainville, before deportation to Auschwitz. Moorehead weaves into her suspenseful, detailed narrative myriad personal stories of friendship, courage and heartbreak. A sound study of research and extensive interviewing.

Read an Excerpt

Read an Excerpt

A Train in Winter - An Extraordinary Story of Women, Friendship, and Resistance in Occupied France By Caroline Moorehead

Chapter One

An enormous toy full of subtleties

What surprised the Parisians, standing in little groups along the Champs-Elysées to watch the German soldiers take over their city in the early hours of 14 June 1940, was how youthful and healthy they looked. Tall, fair, clean shaven, the young men marching to the sounds of a military band to the Arc de Triomphe were observed to be wearing uniforms of good cloth and gleaming boots made of real leather. The coats of the horses pulling the cannons glowed. It seemed not an invasion but a spectacle. Paris itself was calm and almost totally silent. Other than the steady waves of tanks, motorized infantry and troops, nothing moved.

Though it had rained hard on the 13th, the unseasonal great heat of early June had returned. And when they had stopped staring, the Parisians returned to their homes and waited to see what would happen. A spirit of attentisme, of holding on, doing nothing, watching, settled over the city.

The speed of the German victory the Panzers into Luxembourg on 10 May, the Dutch forces annihilated, the Meuse crossed on 13 May, the French army and air force proved obsolete, ill equipped, badly led and fossilized by tradition, the British Expeditionary Force obliged to fall back at Dunkirk, Paris bombed on 3 June had been shocking. Few had been able to take in the fact that a nation whose military valour was epitomized by the battle of Verdun in the First World War and whose defenses had been guaranteed by the supposedly impregnable Maginot line, had been reduced, in just six weeks, to a stage of vassalage. Just what the consequences would be were impossible to see; but they were not long in coming.

By midday on the 14th, General Sturnitz, military commandant of Paris, had set up his headquarters in the Hotel Crillon. Since Paris had been declared an open city there was no destruction. A German flag was hoisted over the Arc de Triomphe, and swastikas raised over the Hôtel de Ville, the Chamber of Deputies, the Senate and the various ministries. Edith Thomas, a young Marxist historian and novelist, said they made her think of 'huge spiders, glutted with blood'. The Grand Palais was turned into a garage for German lorries, the École Polytechnique into a barracks. The Luftwaffe took over the Grand Hotel in the Place de l'Opéra. French signposts came down; German ones went up. French time was advanced by one hour, to bring it into line with Berlin. The German mark was fixed at almost twice its pre-war level. In the hours after the arrival of the occupiers, sixteen people committed suicide, the best known of them Thierry de Martel, inventor in France of neurosurgery, who had fought at Gallipoli.

The first signs of German behaviour were, however, reassuring. All property was to be respected, providing people were obedient to German demands for law and order. Germans were to take control of the telephone exchange and, in due course, of the railways, but the utilities would remain in French hands. The burning of sackfuls of state archives and papers in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, carried out as the Germans arrived, was inconvenient, but not excessively so, as much had been salvaged. General von Brauchtisch, commander-in-chief of the German troops, ordered his men to behave with 'perfect correctness'. When it became apparent that the Parisians were planning no revolt, the curfew, originally set for forty-eight hours, was lifted. The French, who had feared the savagery that had accompanied the invasion of Poland, were relieved. They handed in their weapons, as instructed, accepted that they would henceforth only be able to hunt rabbits with terriers or stoats, and registered their much loved carrier pigeons. The Germans, for their part, were astonished by the French passivity.

When, over the next days and weeks, those who had fled south in a river of cars, bicycles, hay wagons, furniture vans, ice-cream carts, hearses and horse-drawn drays, dragging behind them prams, wheelbarrows and herds of animals, returned, they were amazed by how civilized the conquerors seemed to be. There was something a little shaming about this chain reaction of terror, so reminiscent of the Grand Peur that had driven the French from their homes in the early days of the revolution of 1797. In 1940 it was not, after all, so very terrible. The French were accustomed to occupation; they had endured it, after all, in 1814, 1870 and 1914, and then there had been chaos and looting. Now they found German soldiers in the newly reopened Galeries Lafayette, buying stockings and shoes and scent for which they scrupulously paid, sightseeing in Notre Dame, giving chocolates to small children and offering their seats to elderly women on the métro.

Soup kitchens had been set up by the Germans in various parts of Paris, and under the flowering chestnut trees in the Jardin des Tuileries, military bands played Beethoven. Paris remained eerily silent, not least because the oily black cloud that had enveloped the city after the bombing of the huge petrol dumps in the Seine estuary had wiped out most of the bird population. Hitler, who paid a lightning visit on 28 June, was photographed slapping his knee in delight under the Eiffel Tower. As the painter and photographer Jacques Henri Lartigue remarked, the German conquerors were behaving as if they had just been presented with a wonderful new toy, 'an enormous toy full of subtleties which they do not suspect'.

On 16 June, Paul Reynaud, the Prime Minister who had presided over the French government's flight from Paris to Tours and then to Bordeaux, resigned, handing power to the much loved hero of Verdun, Marshal Pétain. At 12.30 on the 17th, Pétain, his thin, crackling voice reminding Arthur Koestler of a 'skeleton with a chill', announced over the radio that he had agreed to head a new government and that he was asking Germany for an armistice. The French people, he said, were to 'cease fighting' and to cooperate with the German authorities. 'Have confidence in the German soldier!' read posters that soon appeared on every wall. The terms of the armistice, signed after twenty-seven hours of negotiation in the clearing at Rethondes in the forest of Compiègne in which the German military defeat had been signed at the end of the First World War, twenty-two years before, were brutal. The geography of France was redrawn. Forty-nine of France's eighty-seven mainland departments three-fifths of the country were to be occupied by Germany. Alsace and Lorraine were to be annexed. The Germans would control the Atlantic and Channel coasts and all areas of important heavy industry, and have the right to large portions of French raw materials. A heavily guarded 1,200-kilometre demarcation line, cutting France in half and running from close to Geneva in the east, west to near Tours, then south to the Spanish border, was to separate the occupied zone in the north from the 'free zone' in the south, and there would be a 'forbidden zone' in the north and east, ruled by the German High Command in Brussels. An exorbitant daily sum was to be paid over by the French to cover the costs of occupation.

Policing of a demilitarized zone along the Italian border was to be given to the Italians who, not wishing to miss out on the spoils, had declared war on France on 10 June. The French government came to rest in Vichy, a fashionable spa on the right bank of the river Allier in the Auvergne. Here, Pétain and his chief minister, the appeaser and pro-German Pierre Laval, set about putting in place a new French state. On paper at least, it was not a German puppet but a legal, sovereign state with diplomatic relations. During the rapid German advance, some 100,000 French soldiers had been killed in action, 200,000 wounded and 1.8 million others were now making their way into captivity in prisoner-of-war camps in Austria and Germany, but a new France was to rise out of the ashes of the old. 'Follow me,' declared Pétain: 'keep your faith in La France Eternelle'. Pétain was 84 years old. Those who preferred not to follow him scrambled to leave France over the border into Spain and Switzerland or across the Channel and began to group together as the Free French with French nationals from the African colonies who had argued against a negotiated surrender to Germany.

In this France envisaged by Pétain and his Catholic, conservative, authoritarian and often anti-Semitic followers, the country would be purged and purified, returned to a mythical golden age before the French revolution introduced perilous ideas about equality. The new French were to respect their superiors and the values of discipline, hard work and sacrifice and they were to shun the decadent individualism that had, together with Jews, Freemasons, trade unionists, immigrants, gypsies and communists, contributed to the military defeat of the country.

Returning from meeting Hitler at Montoire on 24 October, Pétain declared: 'With honour, and to maintain French unity . . . I am embarking today on the path of collaboration'. Relieved that they would not have to fight, disgusted by the British bombing of the French fleet at anchor in the Algerian port of Mers-el-Kebir, warmed by the thought of their heroic fatherly leader, most French people were happy to join him. But not, as it soon turned out, all of them.

Long before they reached Paris, the Germans had been preparing for the occupation of France. There would be no gauleiter as in the newly annexed Alsace-Lorraine but there would be military rule of a minute and highly bureaucratic kind. Everything from the censorship of the press to the running of the postal services was to be under tight German control. A thousand railway officials arrived to supervise the running of the trains. France was to be regarded as an enemy kept in faiblesse inférieure, a state of dependent weakness, and cut off from the reaches of all Allied forces. It was against this background of collaboration and occupation that the early Resistance began to take shape.

A former scoutmaster and reorganiser of the Luftwaffe, Otto von Stülpnagel, a disciplinarian Prussian with a monocle, was named chief of the Franco-German Armistice Commission. Moving into the Hotel Majestic, he set about organizing the civilian administration of occupied France, with the assistance of German civil servants, rapidly drafted in from Berlin. Von Stülpnagel's powers included both the provisioning and security of the German soldiers and the direction of the French economy. Not far away, in the Hotel Crillon in the rue de Rivoli, General von Sturnitz was busy overseeing day to day life in the capital. In requisitioned hotels and town houses, men in gleaming boots were assisted by young German women secretaries, soon known to the French as 'little grey mice'.

There was, however, another side to the occupation, which was neither as straightforward, nor as reasonable; and nor was it as tightly under the German military command as von Stülpnagel and his men would have liked. This was the whole apparatus of the secret service, with its different branches across the military and the police. After the protests of a number of his generals about the behaviour of the Gestapo in Poland, Hitler had agreed that no SS security police would accompany the invading troops into France. Police powers would be placed in the hands of the military administration alone. However Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, the myopic, thin-lipped 40-year-old Chief of the German Police, who had long dreamt of breeding a master race of Nordic Ayrans, did not wish to see his black-shirted SS excluded. He decided to dispatch to Paris a bridgehead of his own, which he could later use to send in more of his men. Himmler ordered his deputy, Reinhard Heydrich, the cold-blooded head of the Geheime Staatspolizei or Gestapo, which he had built up into an instrument of terror, to include a small group of twenty men, wearing the uniform of the Abwehr's secret military police, and driving vehicles with military plates.

In charge of this party was a 30-year-old journalist with a doctorate in philosophy, called Helmut Knochen. Knochen was a specialist in Jewish repression and spoke some French. After commandeering a house on the avenue Foch with his team of experts in anti-terrorism and Jewish affairs, he called on the Paris Prefecture, where he demanded to be given the dossiers on all German émigrés, all Jews, and all known anti-Nazis. Asked by the military what he was doing, he said he was conducting research into dissidents. Knochen and his men soon became extremely skillful at infiltration, the recruitment of informers and as interrogators. Under him, the German secret services would turn into the most feared German organization in France, permeating every corner of the Nazi system.